by Ruth (Lute) Faleolo

Introduction

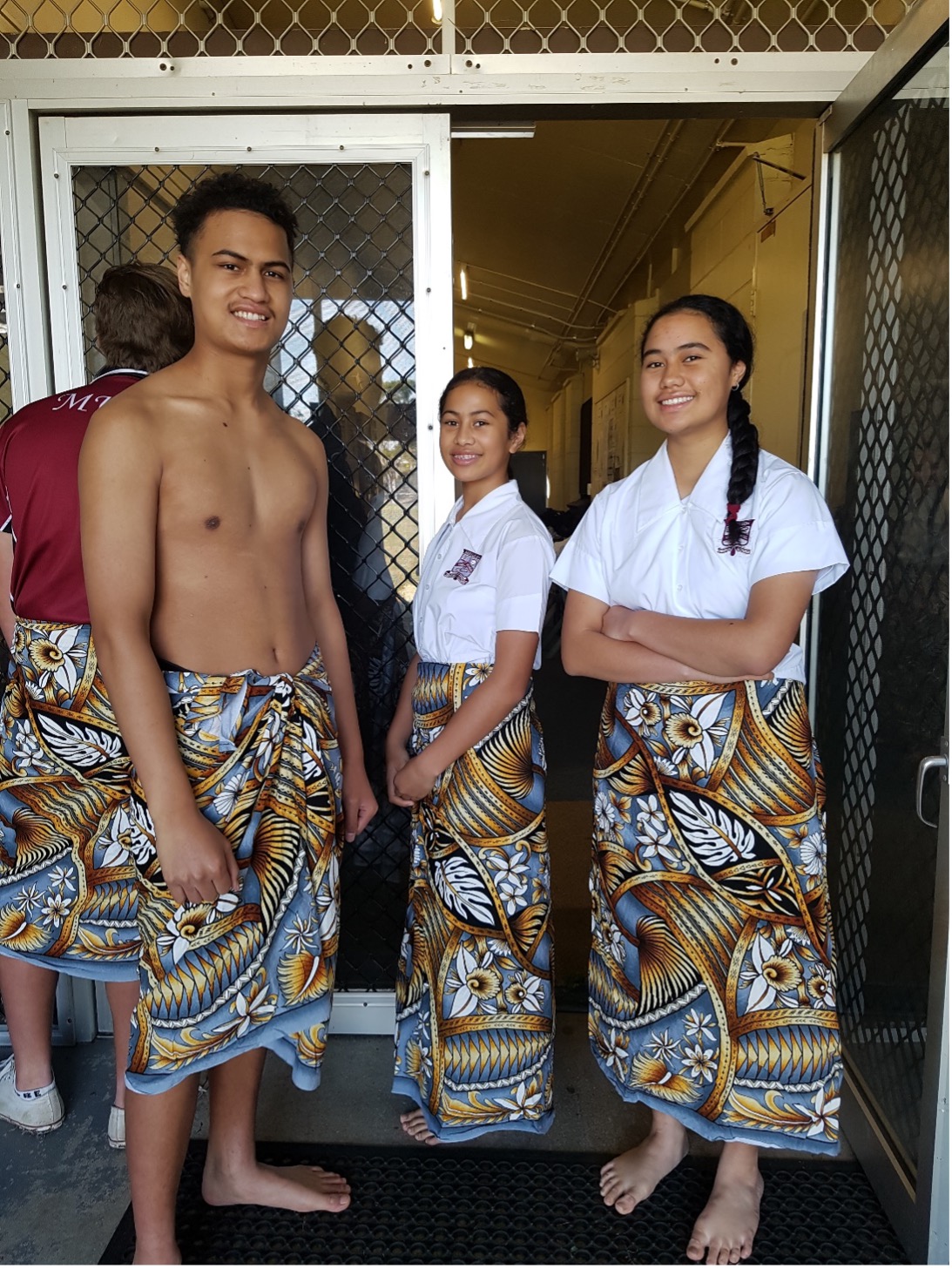

It is important to know who we are and where we come from in order to understand the significance of why we are here. I am Dr. Ruth (Lute) Faleolo. I am the daughter of Rev. ‘Ahoia ‘Ilaiū and Rev. Lose ‘Ilaiū, who left their villages on Tongatapu Island, Tonga in the early 1970s to seek better educational opportunities for their children in Aotearoa/New Zealand (A/NZ). Most of my siblings and I, although born and raised in A/NZ, now live in Australia. My Samoan husband’s parents had similarly moved from Samoa in the 1960s and raised their children in A/NZ. As second-generation Pacific Island parents, we made the decision to raise our children in Australia; as third-generation Pacific Islanders they have seen an improvement in their lifestyles, between A/NZ and Australia. As members of a global Pacific Island community, our children continue to celebrate their cultural heritage understanding that they are an extension of Samoa and Tonga in Australia (see Figure 1). They often speak about further migrations abroad, to America and Europe after their studies are complete. We encourage this as progressive for our collective well-being. These migration narratives are not unique to me or my family. They are a common trans-Tasman migration experience among many Pacific collectives.

As a Pasifika researcher, I have analysed the contemporary migration (1990s onwards) of Pacific Islanders through A/NZ to Australia. Second or third generation Pacific migrants living in Australia can often be misled into thinking that our people are relatively new arrivals to this country. However, this is only in reference to contemporary Pacific Islanders’ movements between their Pacific homelands and the Pacific Rim countries of Australia, A/NZ, and the USA. These movements are only a small portion of the expansive network of interactions and movements between the Pacific homelands and other global destinations which date back to before colonial times; our peoples’ capacity to migrate and network across Oceania supersedes the imaginings and scribblings of colonial historians who have understood and represented our Pacific migration history through a western lens (Banivanua Mar, 2019; Hau‘ofa, 1993; Ka‘ili, 2017; Standfield, 2018; Va‘a, 2001).

‘Epeli Hau’ofa (1939 – 2009), a well-known Tongan and Fijian writer and anthropologist, noted that the natural inclination of Pacific people to migrate has been happening for centuries. Hau‘ofa (1993:156) described the contemporary migration of Pacific people as follows:

Human nature demands space for free movement, and the larger the space the better it is for people. Islanders have broken out of their confinement, are moving around and away from their homelands, not so much because their countries are poor, but because they were unnaturally confined and severed from many of their traditional sources of wealth, and because it is in their blood to be mobile. They are once again enlarging their world, establishing new resource bases and expanded networks for circulation.

Pacific mobilities are ongoing and have been a way of being for Oceanians – kakai mei tahi – long before the arrival of European explorers and their maps of imaginary lines demarcating regional divides. In ancient times and even today, for many Pacific Islanders, these boundaries are meaningless. What remains meaningful for us are our connections and relationships, not divisions, across time and space. Our movements continue to expand the relational spaces – ‘va/vā’- between people and this also means that what we constitute as ‘home’ extends with us in our migration and settlement (Lilomaiava-Doktor, 2009).

How many Pacific Islanders are there in Australia and where do they live?

According to the 2016 Census, there are an estimated 206,000 people with Pacific ancestry living in Australia (not including Maori and Aboriginal). Most live along the Eastern coast, with the highest concentration of Pacific peoples in Queensland, New South Wales, and Victoria (ABS, 2011 cited in Ravulo, 2015:4; Teaiwa, 2019: 385). An influx of Pacific Islanders both directly from the Pacific homelands, and via A/NZ, into Australia, alongside the natural increase of Australian-born Pacific people has seen numbers double over the last three census counts (as shown in Table 1, below).

Census

Pacific Islanders

| 2006 | 2011 | 2016 |

| 112,140 | 150,066 | 206,674 |

Early migration of Pacific people to Australia 1920s–1970s

The Pacific populations in Australia have long identified themselves as part of Australia, within the Oceania region (Ravulo 2015). For instance, during the early 20th century, Pacific groups migrated to Australia for commerce, missionary purposes, and education. Later, in the 1970s the Australian Government sponsored several Pacific scholars to study abroad in Australia. These links with Australia resulted in an increase of Pacific Island immigrants settling in Australia’s urban centres (Aust. Department of Immigration and Citizenship 2017). Furthermore, by the mid-1970s the NZ contract-worker scheme, that had encouraged many Pacific Island labourers to migrate to urban centres like Auckland, ended. This event in A/NZ spurred many Pacific Islanders to travel across the Tasman and settle in Australia (Brown et al. 2012).

Late 1960s – present: Trans-Tasman migration

Since the late 1960s, a significant proportion of Pacific peoples’ migration to Australia has been across the Tasman Sea – via A/NZ. This is part of a general trans-Tasman migration flow of New Zealanders to Australia. There has been a consistent increase in this general trans-Tasman flow since the late 1960s due mainly due to the two countries’ proximity, as well as cultural connections between Australia and A/NZ (Faleolo, 2019; Teaiwa 2019). Trans-Tasman migration is often facilitated by the preferential migration access accorded to New Zealanders under Australia’s migration policy: this is particularly so for Pacific Islanders who are born in A/NZ and thus have A/NZ citizenship or permanent residency rights. Pacific Islanders obtain the rights to travel onwards to Australia because of A/NZ’s visa and citizenship regimes which accord rights to people from many Pacific Island nations based on A/NZ’s own colonial history in the region (something, incidentally, that Australia does not do). A/NZ -born Pacific Islanders sometimes choose to live permanently in Australia after visiting family or take up temporary work contracts and gain Australian citizenship after settling down, getting married, or buying a property in Australia. Over time, policy changes in Australia reveal the ambivalent role of control that government visa schemes and social welfare policies have on the level of access to socioeconomic benefits that Pacific people have. The un-level playing field of social and economic circumstances created by policies have meant that different generations within family groups will either have or lack access to social welfare benefits and student loan schemes.

Why do Pacific Islanders migrate to Australia?

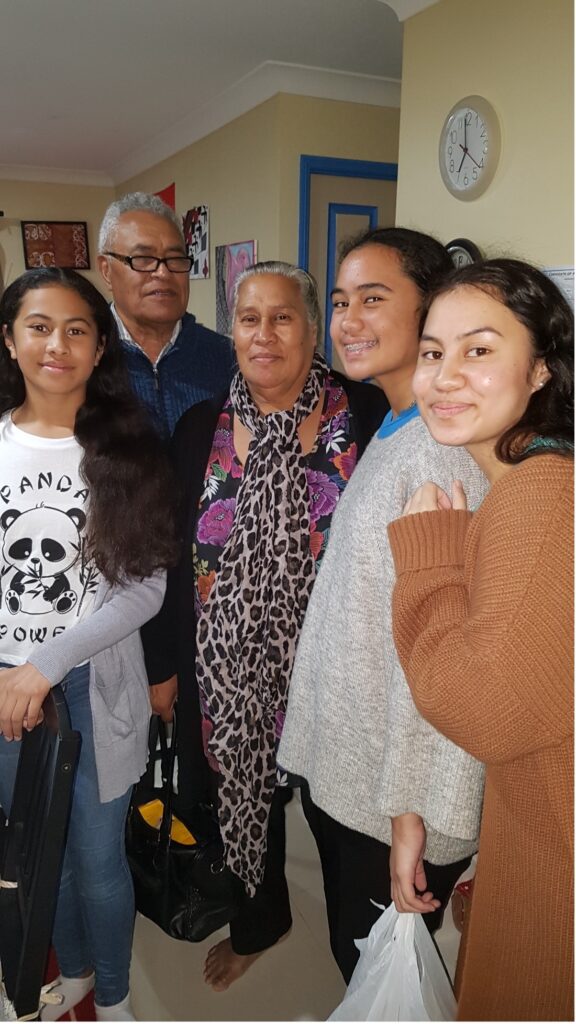

In my 2015-2019 study of Pacific Islander well-being and their trans-Tasman migration (Faleolo, 2020), I found that Pacific Islanders choose to migrate for holistic progress – in my Tongan language this is understood as fakalakalaka fakalukufua. Therefore, the reasons for Pacific migration cannot be understood in purely economic terms. Pacific peoples will almost always prioritise their spiritual and familial/social well-being; these two spheres influence their migration decisions (Enari & Faleolo, 2020). For a Pacific worker, the familial sphere of well-being is maintained through the act of giving and sharing their work outcomes through collectives. Community work, study, and labour outcomes (such as resources, time, talents, skills, and money) are given to help the progress of family members, and often their extended family living abroad or in their Pacific homelands. For instance, owning a family home in Australia (see Figure 2) is seen as a blessing for the family because they can achieve well-being for their immediate or nuclear family. It can also be a blessing to extended family members needing a place to stay during visits from interstate or overseas. Seen in this way, the ownership of property in diaspora solidifies the familial or collective support systems whereby Pacific families enact agency and sustain relationships (va/vā) regardless of a lack of access to social welfare benefits in Australia (Faleolo, 2019: 196).

Migration experiences and well-being perspectives

The following profiles briefly introduce some of the Pasifika people who shared their stories and experiences with me (pseudonyms have been used to protect their identities) during talanoa and e-talanoa that formed part of my research in 2016-2017. These narratives may resonate with you or your parents’ experiences.

‘Akamu

‘Akamu is a 36-year-old man of Samoan descent (born in A/NZ; second generation migrant), who moved to Sydney, Australia in 2003 with hopes to develop his sports career alongside his academic profession. He met and married his Niuean/Samoan wife (born in A/NZ; third generation migrant) and later settled in Brisbane, Australia where he now works as a researcher and social entrepreneur. Overall, ‘Akamu found the change from A/NZ to Australia both a lifestyle change and a mindset change. He and his wife have raised two children with an appreciation for their own Pasifika identities as well as the other diverse cultures that are in Australia and A/NZ. ‘Akamu is optimistic about the plans and purpose that he and his family have in Australia and attribute their success here to God’s guidance and direction in their lives. As a leader in his church and community, he is passionate about building networks of support for other Pacific Islanders living in Australia.

La‘ei

La‘ei is a 29-year-old woman of Samoan descent (born in Samoa; first generation migrant) who moved to A/NZ as a young girl with her parents in 1992. In South Auckland, A/NZ, she had developed a passion for the creative arts while working as a youth leader in her church community. La‘ei moved to Australia in 2014 to pursue a Performing Arts degree. She was successful in finding part-time administration work while she was studying, away from her family and support in A/NZ. She continues to believe that her life seasons are ordained by God; opening the door for her to develop her creative talents in the arts. In the last six years, her work has been seen by thousands of Australians and has toured overseas to other parts of Oceania, America, and Asia.

Pita

Pita is a 35-year-old man of Tongan descent (born in Tonga; first generation migrant) who met and married his Tongan wife in A/NZ before migrating to Australia in 2014. He found permanent work as a labourer and machine operator soon after his move, allowing him and his wife to start saving for their first home. They had always wanted a home for their children but could not afford one in A/NZ. However, to their surprise, house prices in Australia at the time they moved were significantly cheaper. Pita and his wife now have a beautiful home, within their budget, that allows them to put money aside for their children’s education to attend good schools and hopefully university in the near future. Pita feels that their dreams are achievable in Australia and that their choice to migrate from A/NZ was worthwhile. They are now supporting their extended family members, providing accommodation and help to find work in Australia.

Sinamoni

Sinamoni is a 31-year-old female of Tongan descent (born in New Zealand; second generation migrant). In 2011, as newly-weds Sinamoni and her Fijian husband decided to move to Australia to start their new life together. Sinamoni was a postgraduate student who wanted to take advantage of the ‘no fees deal’ for A/NZ citizens living and studying towards a PhD in Australia. Other aspects of living in Australia greatly appealed to Sinamoni and her husband, who was a carpenter. They found that they were able to earn better wages for the same work they carried out in A/NZ. Their higher income has afforded them two homes in Australia, providing themselves and their extended family comfortable and affordable lifestyles.

These narratives reveal the interconnectedness that exists for our Pacific peoples as they migrate to and through Australia. Our migration stories are usually told with our people in mind because our movements are influenced or inspired by the desire to improve our collective well-being as a family or as a network of people (see Figure 3). Pacific migration is rarely a ‘solo act’ and is often carried out with a desire to fulfil the hopes and dreams of our family; a single act through which we as members of a whole are simultaneously satisfied and made complete.

References:

Australian Bureau of Statistics. ‘2006 Census’, ‘2011 Census’ and ‘2016 Census.’ Retrieved 28/11/2019. https://auth.censusdata.abs.gov.au/webapi/jsf/tableView/openTable.xhtml

Banivanua Mar, T. 2019. ‘Boyd’s Blacks: Labour and the making of settler lands in Australia and the Pacific.’ In V. Stead, & J. Altman (Eds.). Labour lines and colonial power: Indigenous and Pacific Islander labour mobility in Australia. (pp.57-73). Canberra, Australia: ANU Press, The Australian National University.

Brown, R.P.C., Leeves, G., & Prayaga, P. 2012. ‘An analysis of recent survey data on the remittances of Pacific Island migrants in Australia,’ Discussion Paper Series 457, School of Economics, University of Queensland, Australia. Retrieved 4/11/2018. http://www.uq.edu.au/economics/abstract/457.pdf

Department of Immigration and Citizenship. n.d. ‘Community information summary: Tongan-born.’ Community Relation, DIAC, Australian Government. Retrieved 5/4/2017. http://www.immi.gov.au/media/publications/statistics/commsumm/source.htm

Enari, D. & Faleolo, R. (2020) Pasifika well-being during the COVID-19 crisis: Samoans and Tongans in Brisbane. Journal of Indigenous Social Development, 110- 127. https://journalhosting.ucalgary.ca/index.php/jisd/article/view/70734/54415

Faleolo, R.L. 2019. ‘Wellbeing perspectives, conceptualisations of work and labour mobility experiences of Pasifika trans-Tasman migrants in Brisbane.’ In V. Stead, & J. Altman (Eds.). Labour lines and colonial power: Indigenous and Pacific Islander labour mobility in Australia. (pp.185-206). Canberra, Australia: ANU Press, The Australian National University.

Faleolo, R.L. 2020. Pasifika well-being and Trans-Tasman migration: A mixed methods analysis of Samoan and Tongan well-being perspectives and experiences in Auckland and Brisbane. (PhD thesis). University of Queensland.

Hau‘ofa, E. 1993. ‘Our sea of islands.’ In E. Hau‘ofa, V. Naidu, & E. Waddell (Eds.). A New Oceania: Rediscovering our sea of Islands (pp.2-17). Suva, Fiji: School of Social and Economic Development, University of the South Pacific.

Ka‘ili, T.O. 2017. Marking indigeneity: The Tongan art of sociospatial relations. Arizona, United States of America: The University of Arizona Press.

Lilomaiava-Doktor, S. 2016. ‘Changing morphology of graves and burials in Samoa,’ Journal of the Polynesian Society 125(2), pp.171-186.

Ravulo, J. 2015. Pacific communities in Australia. Sydney, Australia: University of Western Sydney. Retrieved 31/5/2016. http://www.uws.edu.au/__data/assets/pdf_file/0006/923361/SSP5680_Pacific_Communities_in_Au st_FA_LR.pdf

Standfield, R. 2018. Indigenous mobilities: Across and beyond the Antipodes. Australia: ANU Press.

Teaiwa, K. M. 2019. ‘Niu mana, sport, media and the Australian diaspora.’ In S. Firth & V. Naidu (Eds.). Understanding Oceania: Celebrating the University of the South Pacific and its collaboration with the Australian National University (pp. 381-404). Canberra, Australia: ANU Press.

Va‘a, L.F. 2001. Saili matagi: Samoan migrants in Australia. Suva, Fiji: Institute of Pacific Studies, University of the South Pacific and Iunivesite Aoao o Samoa, National University of Samoa.

Ruth (Lute) Faleolo is a New Zealand-born Tongan, Australian-based Pasifika researcher of Pacific peoples’ migration histories, trans-Pacific mobilities, collective agencies, and multi-sited Pacific e-cultivation of cultural heritage. Her background is in education and social sciences. Ruth’s recent research presents interdisciplinary understandings drawn from a mixed methods study of Trans-Tasman Pasifika well-being perspectives and experiences in Auckland and Brisbane (2015-2020). Ruth’s current post-doctoral study considers Pacific mobilities to and through Australia, and the intersections with Indigenous mobilities in Australia and through New Zealand.